Vitamin B12 Malabsorption: The Commonest Cause of Deficiency

The most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency is malabsorption. In the body, the absorption of vitamin B12 is highly complex and can be disturbed at several points.

Absorption problems significantly reduce the amount of vitamin B12 taken in by the body, even if there is a plentiful dietary supply from food sources. Consequently, vitamin B12 deficiency occurs.

Vitamin B12 Malabsorption Causes

The usual causes of malabsorption are problems and irritations in the gastrointestinal tract and autoimmune reactions against the vitamin B12 transport molecule. With age the body’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 declines in general and therefore absorption problems very frequently occur in old age.

The commonest causes of vitamin B12 malabsorption are:

- Old age

- Inflammation, irritation and disease in the stomach and intestines

- Autoimmune reaction against the B12 transport molecule

- Gastritis, Crohn’s disease

- Parasitic infection such as Helicobacter pylori or tapeworms

- Alcohol, smoking, recreational drugs and medication

- Damage to the liver or pancreas

- Bowel resection

Treating Vitamin B12 Absorption Problems

The treatment of a vitamin B12 malabsorption has two key stages:

- Rectifying vitamin B12 deficiency

Deficiency is treated immediately with vitamin B12 supplements to stop irreparable damage from occurring. - Treating the cause

The problem behind the malabsorption is identified and treated.

Unless parts of the small intestine have been removed, all B12 absorption problems can be treated with oral supplements.

If a severe deficiency or significant symptoms are present, a high dosage initial therapy should be carried out. After this, and in all other cases, a somewhat low dosage maintenance therapy should prove adequate.

| Application | Dosage | Active Ingredient | Finding a Suitable Supplement Online |

| High dose initial therapy | 5000 µg/day for 4 weeks | Hydroxocobalamin | Hydroxocobalamin + high dose + deposit + 5000 µg |

| Maintenance therapy | 1000 µg/day | Methyl-, adenosyl- and hydroxocobalamin | B12 + methylcobalamin + adenosylcobalamin + hydroxocobalamin + 1000 µg + bioactive |

More information: Vitamin B12 Deficiency Treatment and Therapy

Vitamin B12 Absorption

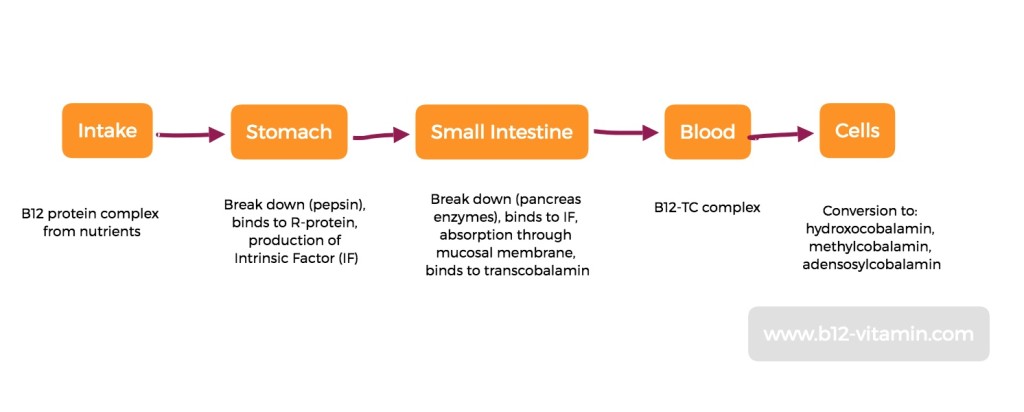

How exactly do vitamin B12 absorption problems occur? In order to better understand this question, we will now look at the path taken by this vital vitamin in our body.

It should first be noted that there are two different intake mechanisms of vitamin B12:

- Active absorption

Intake through specific transport molecules - Passive absorption

Passive diffusion of B12 through the intestinal wall

We will first take a closer look at active absorption, which is especially important for the intake of B12 from food sources.

Release of Vitamin B12 from Food

When we take in vitamin B12 through food, the vitamin is bound to animal proteins. As a result, in the stomach the enzyme pepsin and gastric acid make sure that these proteins are broken down so that the vitamin B12 is released.

B12 now binds to the body’s own transport protein in the stomach, known as R-protein, which allows it to move into the small intestine.

Transportation of Vitamin B12 in the Small Intestine

Special pancreatic enzymes in the small intestine (most significantly, trypsin) split this R-protein complex again and the released vitamin B12 binds to another transport protein – the intrinsic factor, which is produced in the stomach.

Absorption through Intrinsic Factor and Transcobalamin

Intrinsic factor (IF) docks to specific receptors on the intestinal wall, which allow the vitamin to be absorbed through the cell membrane – a process for which calcium is needed. In the endosomes, vitamin B12 is separated from IF by enzymes.

In the cells, the free B12 binds to another transport molecule called transcobalamin II (TC2) and finally makes its way into the bloodstream. In the form of B12-TC2, one portion of the vitamin is transported to the body cells and another binds to two further transcobalamins (TC1 and TC3) and moves into the body’s B12 store in the liver.

Vitamin B12 Conversion into the Bioavailable Vitamin B12 Forms

The B12-TC2 complex that reaches the body’s cells is converted into the vitamin B12 form of hydroxocoblamin inside the cell. In this form, it moves into the cell plasma.

At this stage, the B12 is transformed into two bioactive coenzyme forms: methylcobalamin, which plays an important role in methionine synthase and is required in the cell itself, especially in the cells of the central nervous system; and adenosylcobalamin, which is needed to perform very important functions in the mitochondria – the “energy power plants” of our cells.

Passive Vitamin B12 Absorption without IF

The mechanism described above applies to the active intake of vitamin B12. The situation is different when the intake takes place via injections or the passive diffusion of large oral doses in the small intestine. In both of these instances, the above-described absorption through IF is circumvented and B12 goes directly into the blood.

This also means that the absorbed B12 form stays intact, part of which can be directly absorbed by the cells.

Consequently, these types of intake are utilised in the treatment of vitamin B12 malabsorption.

How Does Vitamin B12 Malabsorption Occur?

Now that we know the path of vitamin B12, it is easier to understand how various absorption problems occur.

In the stomach, a deficiency of pepsin and hydrochloric acid can inhibit B12’s ability to be released from food in the first place, whilst an R-protein deficiency stops the vitamin from being transported intact into the small intestine. The causes of such defects can be disorders of the stomach lining and lack of formation of R-protein and hydrochloric acid by the salivary glands and/or parietal cells in the stomach.

In the small intestine, enzymes from the pancreas, IF from the stomach and calcium from food are needed. Here irritations of the intestinal mucosa, pancreatic diseases, malnutrition and stomach diseases are possible causes for B12 absorption problems.

In the blood, rare genetic disorders can lead to a lack of transcobalamin so that B12 cannot reach the cells. With sufficient transcobalamin, an excess of biologically inactive B12 analogues can lead to the insufficient binding of real vitamin B12 to the transcoblamin, resulting in a B12 deficiency despite good absorption. Especially bacterial migration from the intestine can lead to such excessive concentrations of B12 analogues, but also the consumption of certain algae.

In the cells, certain enzymes are needed again to correctly convert B12 into its coenzyme forms. In particular, various hereditary diseases (cobalamin disease) prevent the required metabolic processes from taking place correctly.

Table: Possible Causes of Vitamin B12 Absorption Problems

Area of the Body | Type of Absorption Problem | Cause |

Stomach | IF deficiency | Chronic atrophic gastritis, |

Acid and pepsin deficiency | Light gastritis (inflammation of the gastric mucosa), medicines | |

Intestines | No intake in the small intestine | Various diseases and irritations of the intestines, |

Pancreas | Lack of pancreatic enzyme | Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic cysts, |

Blood and cells | Disturbed utilisation of B12 | Hereditary diseases, bacterial overgrowth |

Vitamin B12 Malabsorption Treatment

So long as absorption problems are not derived from cobalamin hereditary diseases, or missing parts of the stomach and intestines due to operations, they can usually be treated. Due to the diversity of the condition in question, a description of the individual therapeutic approaches would go far beyond the scope of this article. A change in diet and a regeneration of the intestinal flora would be the first helpful step. In some cases, fungal and bacterial infections are also contributing factors.

Until the absorption disorder has been rectified, vitamin B12 should be taken in high doses through appropriate supplements, in order to rebalance the undersupply.

Vitamin B12 Supplements for People with Absorption Disorders

In the instance of malabsorption, the above factors must be avoided as much as possible. This can be done in two ways:

- High-dose oral supplements

- Injections, which completely circumvent digestion

In the case of an oral intake of high dose B12 through supplements, the entire absorption process in the stomach and intestines can be bypassed, as small amounts of B12 – about 1 percent of the dose – enter the bloodstream via passive diffusion through the intestinal wall. Problems caused by a lack of pepsin, pancreatic enzymes and intrinsic factor can thus be eliminated.

Dosage: 1000 µg per day

Injection: the same effect can be achieved via intramuscular injections of B12. The differences in the efficacy of various active ingredients here have only been compared for hydroxycobalamin and cyanocoblamin, whereby hydroxycobalamin is better absorbed (1, 2). Methylcobalamin has also been shown to be effective, but no comparative studies have been conducted.

Dosage: 1000 µg hydroxocobalamin every 8 weeks

Active Ingredients

If taken orally, the direct use of the natural and bioactive B12 forms – methylcobalamin, adenosylcobalamin and hydroxocobalamin – is recommended.

For injections, only the active ingredients hydroxocobalamin and cyanocobalamin are available. The former shows a much better bioavailability than the latter. In the case of genetic disorders, the active ingredient cyanocobalamin has no effect at all; whereas hydroxocobalamin remains effective in the case of some of these disorders (3).

Source

1. Keith Boddy, et al. Retention of cyanocobalamin, hydroxocobalamin, and coenzyme b12 after parenteral administration. The Lancet, Volume 292, Issue 7570, 28 September 1968, Pages 710–712

2. Hertz, H., Kristensen, H. P. Ø. and Hoff-JØrgensen, E. (1964), Studies on Vitamin B12 Retention Comparison of Retention Following Intramuscular Injection of Cyanocobalamin and Hydroxocobalamin. Scandinavian Journal of Haematology, 1: 5–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1964.tb00001.x

3. Hans C. Andersson, MD, Emmanuel Shapira, MD, PhD Biochemical and clinical response to hydroxocobalamin versus cyanocobalamin treatment in patients with methylmalonic acidemia and homocystinuria (cblC) The Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 132, Issue 1, January 1998, Pages 121–124