Vitamin B12 Foods

This article gives a comprehensive overview of food sources of vitamin B12 and will provide detailed answers to the following questions:

Contents

|

| For anyone looking only for an overview of the B12 content in foods |

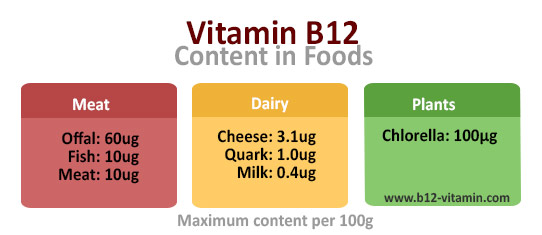

The Prevalence of Vitamin B12 in Foods

Humans are dependent on a regular supply of vitamin B12 through the foods they eat, in order to remain healthy. But which foods contain a significant amount of this essential vitamin?

Unfortunately, unlike many other vitamins, B12 is found in high quantities in very few foods. This article will provide an overview of the food sources of B12 that can be used to obtain the recommended daily intake of the vitamin (2.4 µg).

Which Food Groups Contain Vitamin B12?

Animal products

Vitamin B12 is created by special microorganisms and is found almost exclusively in animal products – such as fish, meat, dairy and eggs.

Plant-based foods

Plant-based produce, which are the sources for most of the other vitamins we need, contain almost no B12 – whether fruit, vegetables, nuts or seeds. Only fermented plant foods, such as sauerkraut and beer, as well as an algae called chlorella contain small amounts of the vitamin.

However, to cover the B12 requirement with these foods is only possible with very good health and highly effective absorption in the gut. In all other cases, obtaining a supply through B12 supplements is safer, more comfortable and usually more economical.

Do You Eat Enough Vitamin B12-Rich Foods?

There are multiple health benefits to securing a steady supply of vitamin B12. Yet whether or not a person can obtain this supply through their diet alone depends on three key factors:

- The B12 content in the foods they eat

- The absorption ability of their body

- Their individual bodily needs

In most cases, vitamin B12 deficiency emerges not through a deficient dietary supply of vitamin B12, but through either malabsorption or an increased requirement of the vitamin due to stress and environmental pollution.

Malabsorption

Vitamin B12 is absorbed via the intestinal mucosa. The health of the stomach and intestines is slightly to severely impaired in many people in the Western industrialised world, so that many people cannot absorb B12 well from food. Recent studies suggest that B12 deficiency could affect up to 39 percent of the population (1).

It is not possible to determine how good the B12 supply is in specific foods from the official content of the vitamin alone. Even with regular meat consumption, a vitamin B12 deficiency can easily arise. This is because some of the B12 in food can be lost through frying and contact to light, so that through cooking and other preparations, the B12 content sharply decreases (4).

Vegetarian or vegan diets increase the risk of B12 deficiency even more, as hardly any plant-based foods naturally contain the vitamin (2).

Increased Requirement

Stress, illness, pollution and many other factors can contribute to a severely increased requirement for B12. In such cases, vitamin intake from food may also not be enough to stay healthy.

Active and Passive Intake of B12 from Foods

The reasons for problems regarding the absorption of B12 can be found in the biological mechanisms through which the body absorbs the vitamin.

Active intake

For its absorption, vitamin B12 requires a special endogenous molecule called intrinsic factor. In this way, no more than about 2 μg of vitamin B12 can be ingested per meal. Therefore, when obtaining B12 from food, people rely on taking B12 several times a day, in order to meet their total requirement (3).

A single meal, for example, containing a food very rich in B12 – such as offal – brings little advantage over other lower-concentration B12 sources. In one meal there is a limited amount of the vitamin that can anyway be absorbed.

Passive intake

Only with a far higher dosages than that which usually occurs in foods can the body absorb more B12 through passive diffusion. Here B12 supplements are advantageous; the vitamin in supplements is of a higher dosage and so can be absorbed passively in the intestines without intrinsic factor.

When is Vitamin B12 from Food not Sufficient?

In optimal health, an omnivorous and in some cases vegetarian diet will provide enough vitamin B12.

This is often not possible however in the following cases:

- Stress (= higher B12 requirement)

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Regular intake of various medicines

- Alcohol and cigarette consumption

- Pregnancy and whilst breastfeeding

- Old age

- Utilisation disorders

- Disease and infection

- General unhealthy diets

Under such circumstances, an individual should consume the following amounts of vitamin B12 through supplements:

| Purpose | Profile | Recommended Daily Dosage | |

| Low additional requirement | Provides half the daily requirement of a healthy individual. |

| 10 µg |

| Full supplementary requirement | Provides the total daily requirement of a healthy individual. |

| 250 µg |

| Increased additional requirement | Provides the total daily requirement for those with an increased B12 need. |

| 500 µg |

| High dose vitamin B12 | Provides the daily requirement for people with a significantly higher B12 need and absorption problems. |

| 1000 µg |

For more information on how much B12 to take, see our article: Vitamin B12 Dosages

If you are interested in checking your vitamin B12 status, there are details on how in our article: Vitamin B12 Deficiency Test

Vitamin B12 Forms in Foods

Different types of B12 exists. In foods, the following forms of the vitamin are found (2):

- Methylcobalamin (mainly in cheese)

- Hydroxocobalamin (all foods)

- Adenosylcobalamin (meat, dairy)

The synthetic form of B12 called cyanocobalamin, used in the cheapest supplements, does not occur in natural produce. In supplements today, mainly the natural forms of B12 – methyl-, adenosyl- and hydroxocobalamin – are used, either individually or combined.

Detailed information on the differences of the various types of B12 can be found in our article: Vitamin B12 Forms.

Interim Conclusion

|

In the following, the B12 content in individual foods will be examined in detail.

Vitamin B12 in Animals

Vitamin B12 is produced both in animals and in humans by microorganisms that live mainly in the colon. Unfortunately, the point at which this occurs is beyond where absorption takes place in the small intestine; most of this vitamin B12 is excreted unused and most animals rely on a dietary supply of the vitamin just like humans. An exception are ruminants, or grazing animals, which can self-produce the vitamin in their rumen.

Carnivorous animals take in B12 through the meat of their prey, whilst non-ruminant herbivores obtain the vitamin through the combination of their food with soil and faeces.

The daily dose does not necessarily have to be reached every day: like humans, animals also store a supply of vitamin B12 in their liver. This reserve is consumed only very slowly, so that a temporary shortage can be compensated for over several years. Nevertheless, a regular intake of the vitamin is recommended, as the first symptoms of a deficiency may occur even whilst the store is being emptied.

The largest occurrence of vitamin B12 in animal foods is thus found mainly in the intestines – in particular the point where the vitamin is produced, as well as in the liver where it is stored. The concentration of B12 progressively decreases from organs to lean meat, and then to milk or eggs. Nevertheless, some cheeses, such as camembert, may still contain quite large amounts of B12 due to how they are produced.

Vitamin B12 Foods: Dairy vs Meat

Various studies have shown that vitamin B12 is better absorbed from cheese and fish than from meat and eggs (1, 5). This is due to a number of reasons:

Firstly, vitamin B12 is heat sensitive and a large amount of vitamins are lost through cooking.

Secondly, because it binds to proteins in food; the easier it is to digest, the better absorbed the B12.

Thirdly, the intrinsic factor (IF) – a special molecule required for the intake of vitamin B12 – can only absorb a maximum of 1.5 – 2.0 μg of the vitamin per meal. As a result, the high vitamin B12 content in meat does not carry significant benefits if consumed in a single meal.

Vegetarian Sources of Vitamin B12

Those who do not eat meat but consume animal products such as milk, cheese and eggs still have some foods in their diet containing sufficient vitamin B12.

Camembert, emmental and gouda cheese – as well as eggs from chickens – are the vegetarian foods with the highest B12 content. Milk and yoghurt, on the other hand, only contain small quantities of the vitamin. Even so, the absorption of vitamin B12 from dairy products seems to be easier for our bodies than from eggs (6).

Vegan Sources of Vitamin B12

Plants cannot produce vitamin B12; nonetheless sometimes it is detected in very small amounts in different species. The explanation here is simple: in natural agriculture, humus contains many microorganisms, some of which produce the vitamin. Some plants can thus absorb small amounts of B12 from the soil and store it for a short time. However, the content is very low and greatly fluctuates, so that despite this mechanism, plants are not a reliable source of vitamin B12.

Even through the soil itself, which sticks to the surface of the plant, people can consume B12 when eating some plant foods – for example, fresh carrots. However, the washing of vegetables is always recommended, which more or less eradicates this source.

In industrial agriculture, the humus is usually so destroyed by chemicals and overuse that hardly any microorganisms can be found in the soil.

More information about vitamin B12 in the vegetarian/vegan diet can be found in our article: Vitamin B12 for Vegetarians and Vegans.

The Only Plant-Based Source of Vitamin B12: Algae

Some algae contain vitamin B12, but there is still a lot of misinformation in circulation. When this source of B12 was discovered, mostly old measuring methods were used to determine the exact vitamin content, which also detect substances similar to B12 (known as vitamin B12 analogues). These substances, also called “pseudo vitamin B12”, are not only ineffective, they actually exacerbate vitamin B12 deficiency.

The content and bioavailability of different algae has been highly controversial for a long time (7, 8). Today the alga chlorella is the only reliable source of B12 (9). The content is still above all animal sources with 80 μg of B12 per 100 g. This sounds like a lot at first – but it is important to bare in mind that you usually consume only a very small amounts of algae. Therefore, hardly more than 1.5 μg of the vitamin are absorbed per serving. If taken several times a day, for healthy individuals the algae can help maintain a general B12 supply, which is composed of several sources.

However, it is not a suitable substitute for B12 supplements in the case of deficiency, increased requirement or absorption disorders.

Further information: Vitamin B12 in Algae.

Vitamin B12 Table

Foods with High Vitamin B12 Content

| Foodstuff | Content in μg / 100g | % of recommended daily requirement of B12 (adults) |

|---|---|---|

| Beef liver | 65.0 | 2167% |

| Calf liver | 60.0 | 2000% |

| Lamb liver | 35.0 | 1169% |

| Caviar | 16.0 | 533% |

| Oysters | 14.5 | 483% |

| Liver sausage, fine | 13.5 | 450% |

| Rabbit | 10.0 | 333% |

| Liver dumplings | 10.0 | 333% |

| Mackerel | 9.0 | 300% |

| Herring | 8.5 | 283% |

| Mussels | 8.5 | 283% |

| Lean beef | 5.0 | 167% |

| Wild boar | 5.0 | 167% |

| Trout | 4.5 | 150% |

| Thuna | 4.3 | 143% |

| Goose | 4.0 | 133% |

| Perch | 3.8 | 126% |

| Saithe (Pollock) | 3.5 | 116% |

| Camembert | 3.1 | 103% |

| Emmental | 3.1 | 103% |

| Lamb | 3.0 | 100% |

| Duck, breast | 3.0 | 100% |

Foods with Medium Vitamin B12 Content

| Foodstuff | Content in µg / 100g | % of recommended daily requirement of B12 (adults) |

| Salmon | 2.9 | 97% |

| Cephalopods (squid/octopus) | 2.5 | 83% |

| Pork cutlet | 2.1 | 70% |

| Edam cheese | 2.0 | 67% |

| Parmesan | 2.0 | 67% |

| Lean veal | 2.0 | 67% |

| Pike | 2.0 | 67% |

| Egg yolk (chickens) | 2.0 | 67% |

| Gouda | 1.9 | 63% |

| Eggs (chickens) | 1.8 | 60% |

| Gyro | 1.6 | 53% |

| Plaice | 1.5 | 50% |

| Mince | 1.5 | 50% |

| Mortadella | 1.4 | 46% |

| Salami | 1.4 | 46% |

| Pork sausage | 1.3 | 43% |

| Mozzarella | 1.3 | 43% |

| Frankfurter sausage | 1.1 | 36% |

| Lean pork | 1.0 | 33% |

| Cream cheese (min. 10% fat) | 1.0 | 33% |

| Quark | 0.9 | 30% |

| Fish fingers | 0.8 | 26% |

| Cottage cheese | 0.7 | 23% |

| Anchovies | 0.6 | 20% |

| Sheep’s milk | 0.5 | 17% |

| Chicken | 0.4 | 13% |

| Cow’s milk | 0.4 | 13% |

| Yoghurt | 0.4 | 13% |

| Sheep’s cheese (feta) | 0.4 | 13% |

| Egg white (chicken) | 0.1 | 3% |

| Goat’s milk | 0.1 | 3% |

| Wheat beer | 0.1 | 3% |

Foods with no Vitamin B12 Content

| Foodstuff | Content in µg / 100g | % of recommended daily requirement of B12 (adults) |

| Vegetables | 0 | |

| Fruits | 0 | |

| Plant fats and oils | 0 | |

| Pulses (beans, peas, etc.) | 0 | |

| Herbs | 0 | |

| Nuts and seeds | 0 | |

| Cereals/wheat | 0 | |

| Amaranth | 0 | |

| Quinoa | 0 | |

| Rice | 0 |

Sources

- Judy McBride (2). B12 Deficiency May Be More Widespread Than Thought. Agricultural Research Service. United States Department of Agriculture. http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/2000/000802.htm (Stand 05/2015)

- Pawlak, Roman, et al. How prevalent is vitamin B12 deficiency among vegetarians?. Nutrition reviews, 2013, 71. Jg., Nr. 2, S. 110-117.

- Abels, J., Vegter, J. J. M., Woldring, M. G., Jans, J. H. and Nieweg, H. O. (1959), The Physiologic Mechanism of Vitamin B12 Absorption. Acta Medica Scandinavica, 165: 105–113.

- Malgorzata Czerwonka, Arkadiusz Szterk, Bozena Waszkiewicz-Robak, Vitamin B12 content in raw and cooked beef, Meat Science, Volume 96, Issue 3, March 2014, Pages 1371-1375, ISSN 0309-1740,

- Vogiatzoglou A, Smith AD, Nurk E, et al. Dietary sources of vitamin B-12 and their association with plasma vitamin B-12 concentrations in the general population: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1078–87.

- Tucker KL, Rich S, Rosenberg I, et al . Plasma vitamin B-12 concentrations relate to intake source in the Framingham Offspring study. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71:514–22

- Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007 Nov;232(10):1266-74. Review. PubMed PMID: 17959839.

- Dagnelie PC, van Staveren WA, van den Berg H. Vitamin B-12 from algae appears not to be bioavailable. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991 Mar;53(3):695-7. Erratum in: Am J Clin Nutr 1991 Apr;53(4):988. PubMed PMID: 2000824.

- J. H. Chen, S. J. Jiang: Determination of cobalamin in nutritive supplements and Chlorella foods by capillary electrophoresis-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem, 2008, 56(4), 1210-5

- Prof. Dr. Helmut Heseker, Dipl. oec. troph. Beate Heseker; Die Nährwerttabelle, 2. Aufl., 2012, Neuer Umschau Buchverlag