Vitamin B12 – Vital for the Brain and Psyche

Vitamin B12 is required for a number of biological processes that are essential to the central nervous system and for neural maintenance, and thus the vitamin has a major influence on the health of the brain and psyche. As a result, vitamin B12 deficiency does not only temporarily severely impair brain activity, but can also lead to long-term structural damage.

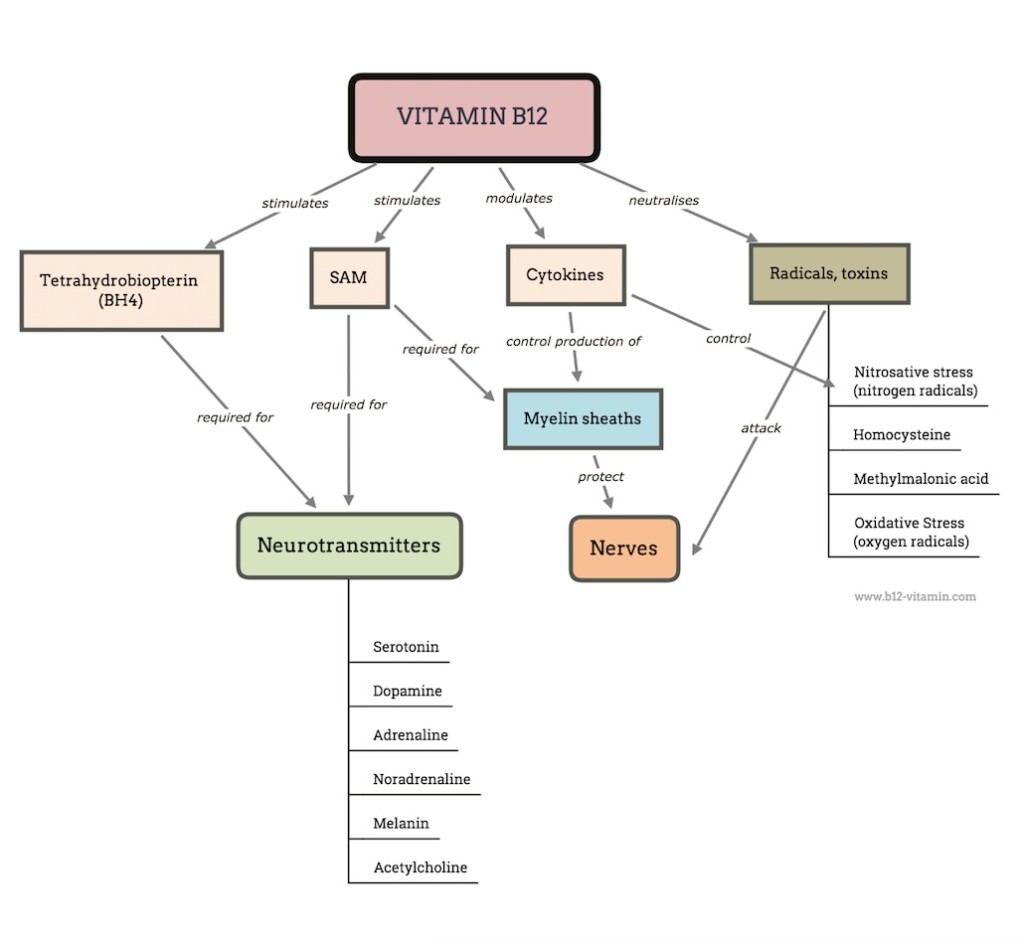

The vital importance of this vitamin to the brain and psyche are further illuminated by some of the key benefits of B12 in this area, which include:

- Supporting the development and protection of the neural connections in the brain

- Encouraging the synthesis of vital chemical messengers in the brain

- Counteracting various neurotoxic substances in the brain

- Regulating crucial cytokines in the central nervous system

In this way, B12 is intrinsically linked to mood, cognitive performance, memory, perceptions, coordination and many other fundamental processes in the brain. It is therefore today regarded as one of the most important vitamins for the psyche.

Vitamin B12 Deficiency – Psychological Symptoms

Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to diverse psychological symptoms. Among the most common are:

- Dementia

- Memory loss

- Cognitive decline

- Cognitive disorders

- Severe poor concentration

- Depression

- Schizophrenia

- Mania

- Katatonia

- Paranoia

- Psychosis

- Delusions

- Delirium

Sometimes these symptoms can be fully or partially treated with vitamin B12 (1). It is important to bear in mind, however, that there are many alternative causes to these symptoms and that they are often triggered by a number of factors in combination. Consequently, taking B12 is not always effective.

These symptoms often occur before a B12 deficiency is clearly detectible in the blood, which is why the serum level for vitamin B12 is no longer considered a reliable marker (2, 3).

The Best Vitamin B12 Level for Mental Health

Many researchers are now of the opinion that the current recommendations for B12 are much too low. They are based solely on the symptom of anemia and do not take into account more recent findings on the extensive effects of the vitamin.

Research has shown that the decisive factor for psychological symptoms is not the level of B12 in the blood serum but in the cerebrospinal fluid (4, 5). Various studies indicate that a sufficient concentration in the brain and spinal cord is only reached with B12 levels around 600 pg/ml (6).

This explains why psychological symptoms often occur long before the blood count changes or the conventional limits for B12 deficiency are reached (which define deficiency as a level of/below 200-300 pg/ml).

In psychiatric patients, it is therefore advisable to both increase blood values above 600 pg/ml and reduce the secondary markers, methylmalonic acid and homocysteine.

Vitamin B12 and Neural Development

B12 is particularly vital to the early development of the brain and nervous system in the womb and first years of life. If women are B12 deficient whilst pregnant or breastfeeding, it can lead to serious development problems in the child’s brain (7).

Symptoms include:

- Developmental delays

- Anemia

- Loss of appetite

- Chronic vomiting

- Weight loss

- Low brain volume/atrophy

- Palsy/cramps

- Apathy

- Irritability

The resulting damage is not always reversible, which is why an adequate B12 intake during pregnancy is critical. Especially women who are vegan/vegetarian, diabetic or have gastrointestinal problems should pay close attention to maintaining a good supply of the vitamin. This is often only possible with B12 supplements.

How Effective is Vitamin B12 for Psychological Disorders and Illnesses?

The utilisation of vitamins and nutrients in general has unfortunately not yet found its place in standard psychiatric practice. This is all the more unfortunate when you consider the strong medications that are being prescribed more and more frequently that sometimes majorly interfere with the sensitive chemical balance of the brain, the long-term consequences of which are extremely questionable.

The scientific literature shows countless impressive case reports in which even the most severe mental disorders have been remedied with vitamin B12 alone. Also in the messages we have received from readers of this website, there are some very impressive experience reports. In some cases, the detection and treatment of a B12 deficiency can end many years of dependence on medicines or even institutionalisation.

As described above, however, the causes of many mental disorders are complex; no nutrients can be considered a miracle cure in this context, mainly because there are often several deficiencies and factors present at the same time. This makes research all the more difficult.

Methylcobalamin and Methylfolate

It is not yet clear through which mechanisms vitamin B12 has an effect on different mental health diseases. However, it is probably methylcobalamin that plays the key role here.

This theory is supported by the fact that vitamin B12 often only produces successful results if it is combined with methylfolate (L-5-MTHF, metafolin, quatrefolic).

Key Points:

|

Vitamin B12 for Psychological Symptoms

The following dietary supplements can be recommended for mild psychological symptoms.

Vitamin | Dose | Active Ingredient |

B12 | 1000 µg | Natural forms: methylcobalamin, adenosylcobalamin, hydroxocobalamin |

Folate | 400 µg | L-5-MTHF, quatrefolic |

For in-depth information on different vitamin B12 supplement dosages, click here.

Below we will give brief overviews of the research into individual psychological diseases, exploring their connections to vitamin B12.

Vitamin B12 and Depression

Low B12 levels have been associated with depression in several studies (8); improvements to treatment outcomes due to high B12 levels have also been reported (9). Various researchers have therefore repeatedly called for B12 to be given more focus in the field of depression research (10).

In intervention studies however, B12 has not been shown to bring about any clear improvements, as demonstrated by a meta-analysis from 2015 (11). It is also possible, however, that insufficient doses and missing cofactors are behind these ambiguous results. In some cases, doses below 500 µg were administered, which are too low to be successful in the case of absorption disorders. On the other hand, recent research shows that depression is probably a sign of severe inflammation in the body and thus B12 is only one nutrient that can combat this.

In this context, one of the possible therapeutic workings of the vitamin is due to how it stimulates the production of SAM, which has a direct anti-inflammatory function and is proven to be very effective against depression (12, 13). Here B12 works in combination with folic acid and can only be successful when there are sufficient supplies of both vitamins.

This is further complicated by the fact that a large proportion of clinically depressed patients have a genetic mutation that interferes with the conversion of folic acid into active folate (14 -16). People with this so-called MTHFR mutation depend on an intake of folate in the active form methylfolate (L-5-MTHF), which has also been shown to be effective for depression (17).

It would therefore be interesting to conduct studies which investigate the connection between B12 and methylfolate.

Vitamin B12 and Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a similar case (18). Here, vitamin B12 and methylfolate seem to have an interrelated effect (19). Deficiency of both B12 and folate leads to an increase in the homocysteine level in the blood. Several studies have identified an elevated homocysteine level as a major risk factor for schizophrenia. Here too, the above-mentioned MTHFR mutation plays a major role, and methylfolate (21, 22) has produced correspondingly good results in treatment (23).

Therapy with B12 and folic acid has brought clear improvements to the symptoms of schizophrenia in several studies (24, 26).

A study from 2016 showed that people suffering from schizophrenia had significantly reduced levels of methylcobalamin in the cerebrospinal fluid, while the fluctuations in the blood were far less pronounced. It is still unclear which mechanisms are responsible for the regulation of B12 in the brain, although it is suspected that the blood-brain barrier is disturbed. This observation supports the hypothesis that a lack of methylcobalamin is involved in the development of schizophrenia.

Vitamin B12 and Psychoses

Psychoses are a recognised symptom of B12 deficiency; the connection has been known and well researched for almost 100 years – up to the exact presentation of the interrelated EEG abnormalities (27, 28).

Psychoses caused by B12 deficiency respond well to the vitamin and can in some cases be completely treated (29, 30). It is astonishing that psychosis can be the symptom of a B12 deficiency. The vitamin can achieve better treatment results here than conventional anti-psychotic drugs (31). In this context, hydroxocobalamin has been shown to be as effective as methylcobalamin.

Here too, there are many indications that it is not the B12 concentration in the blood that is decisive, but that in the cerebrospinal fluid, as has already been discussed above in relation to schizophrenia (32). The exact mechanism however remains unclear.

Vitamin B12, Mania and Bipolar Disorder

The connection between B12 deficiency and manic symptoms is almost equally well documented. Numerous case studies show that severe manic conditions can be treated quickly and efficiently with the vitamin (33 – 36).

While the exact correlation here remains unknown, the main cause is suspected to be damage to the myelin sheaths of the brain’s white matter (37).

This theory remains under investigation, however, since the symptoms are reversible, which is unlikely in the case of structural myelin damage.

Vitamin B12 and Dementia

The association between vitamin B12, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease has received broad scientific attention. Numerous studies have shown a statistical link between low B12 levels and the loss of cognitive abilities (38 – 40). It could also be shown that low levels of the vitamin precede the development of such diseases, although no causality has yet been proven (41, 42).

Unfortunately, the therapeutic potential of B12 in this area appears to be very limited, as there seems to be only a narrow timeframe in which B12 can halt cognitive decline. Several studies have shown that this timeframe is about 6-12 months after the onset of the first symptoms (43 – 45).

After this period, the damage appears to be irreparable, at least with B12. Here, too, structural damage caused by a B12 deficiency seems to be decisive.

For an in-depth discussion of this topic, see the article: Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Dementia

Vitamin B12’s Effect on the Psyche

All of vitamin B12’s functions probably play a major role in connection to mental health conditions, although it is not exactly clear which mechanisms are responsible for which symptoms.

However, it is likely that reversible symptoms such as depression or psychosis are primarily due to chemical interactions; whilst the irreparable nature of many forms of dementia tends to indicate the permanent destruction of nerves.

Vitamin B12 and Neurotransmitters

Vitamin B12 contributes in two ways to the synthesis and function of what are known as the monoamine neurotransmitters, which operate both as hormones and neurotransmitters (messengers in the nervous system):

- B12 stimulates the creation of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an important coenzyme of neurotransmitter synthesis (46, 47)

- B12 is needed for the synthesis of methionine, which is further converted into S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and also plays a role in the synthesis of some neurotransmitters (48 – 50)

Some of the neurotransmitters influenced by the vitamin are:

- Dopamine

- Adrenaline

- Noradrenaline

- Melatonin

- Serotonin

In addition, vitamin B12 influences

- Acetylcholine

All of these neurotransmitters and hormones perform important functions in the central nervous system and have a major impact on perception, mood and cognitive processing.

Vitamin B12 and Nerve Protection

B12 deficiency can lead not only to chemical changes in the brain, but also to the permanent structural loss of nerves, brain mass and neuronal connections. Such damage cannot always be mended.

One of the main mechanisms for this is the B12-dependent regeneration of the myelin sheaths, a fat-rich protective layer around the nerve cords, which maintains nerve conductivity on the one hand, and protects the nerves from neurotoxic substances, radicals and toxins, on the other.

Both methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin are involved in the composition of the myelin sheaths.

A detailed discussion of this topic can be found in our article: Vitamin B12 and Nerves.

Vitamin B12: Opponent of Homocysteine, MMA and Radicals

Vitamin B12 is also an important antagonist of some neurotoxic and/or pro-inflammatory substances, which include:

- Homocysteine

Methylcobalamin promotes the conversion of homocysteine to methionine - Methylmalonic acid (MMA)

Adenosylcoabalamin encourages the conversion of MMA - Nitrogen radicals

Vitamin B12 – especially hydroxocobalamin – is a scavenger of nitrogen (NO) radicals and also regulates their synthesis (51, 52) - Oxygen radicals

Reduced cobalamin is a scavenger of superoxide and other oxygen radicals (53 – 55)

All of these substances either directly attack the nerves and brain, or promote chronic inflammations that lead to nerve damage.

While for a long time these functions of B12 have received little attention, in the last 10 years they have moved more into focus. B12’s workings in this area should no longer be underestimated.

Vitamin B12 and Cytokines

Fairly new is the discovery that B12 has effects that go way beyond its role as a cofactor in metabolic reactions. Several studies have shown that the vitamin has a hormone-like effect on special messengers called cytokines by down-regulating the levels of certain cytokines and raising those of others (56 – 59).

The cytokines involved have important functions for the protection and preservation of nerves and the brain, for example by reducing inflammations or stimulating the production of radical scavengers.

Conclusion: Vitamin B12, Brain and Psyche

As numerous case reports show, B12 deficiency can have devastating effects on mental health. While in some instances the corresponding symptoms can be completely treated with the vitamin; more long-term deficiencies appear to cause permanent damage.

This illustrates the enormous preventive importance of maintaining sufficient B12 levels, as well as the fascinating therapeutic potential of the vitamin.

Groups at risk – such as vegetarians/vegans, pregnant and breastfeeding women, the chronically ill and the elderly – are strongly advised to take B12 supplements.

Sources

- Geagea K and Ananth J. Response of a psychiatric patient to vitamin-B12 therapy. Diseases of the Nervous System 36, 3: 342-344, 1975.

- Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al: Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 1720 –1728

- Healton EB, Savage DG, Brust JC, et al: Neurologic aspects of cobalamin deficiency. Medicine (Baltimore) 1991; 70:229–245

- Mitsuyama Y and Kogoh H. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid vitamin B12 levels in demented patients with CH3- B12 treatment – preliminary study. Japanese Journal of Psychiatry and Neurology 42, 1: 65 -71, 1988.

- VanTiggelen CJM, Peperkamp JPC and TerToolen JFW. Vitamin-B12 levels of cerebrospinal fluid in patients with organic mental disorder. Journal of Orthomolecular Psychiatry 12: 305-311, 1983.

- Dommisse, J. (1991). Subtle vitamin-B12 deficiency and psychiatry: a largely unnoticed but devastating relationship?. Medical hypotheses, 34(2), 131-140.

- Dror, D. K., & Allen, L. H. (2008). Effect of vitamin B12 deficiency on neurodevelopment in infants: current knowledge and possible mechanisms. Nutrition reviews, 66(5), 250-255.

- Tiemeier H, van Tuijl HR, Hofman A, et al: Vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine in depression: The Rotterdam Study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:2099–2101

- Hintikka J, Tolmunen T, Tanskanen A, et al: High vitamin B12 level and good treatment outcome may be associated in major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2003; 3:17

- Coppen, A., & Bolander-Gouaille, C. (2005). Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 19(1), 59-65.

- Almeida, O.P., Ford, A.H. and Flicker, L. (2015) ‘Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials of folate and vitamin B12 for depression’, International Psychogeriatrics, 27(5), pp. 77–737

- Mischoulon, D., & Fava, M. (2002). Role of S-adenosyl-L-methionine in the treatment of depression: a review of the evidence. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 76(5), 1158S-1161S.

- Papakostas, G. I., Alpert, J. E., & Fava, M. (2003). S-adenosyl-methionine in depression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Current psychiatry reports, 5(6), 460-466.

- Hickie I, Scott E, Naismith S, Ward PB, Turner K, Parker G, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K. Late-onset depression: genetic, vascular and clinical contributions. Psychol Med. 2001 Nov;31(8):1403-12.

- Gilbody, S., Lewis, S., & Lightfoot, T. (2007). Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. American journal of epidemiology, 165(1), 1-13.

- Bjelland, I., Tell, G. S., Vollset, S. E., Refsum, H., & Ueland, P. M. (2003). Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and the MTHFR 677C? T polymorphism in anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(6), 618-626.

- Stahl, S. M. (2007). Novel therapeutics for depression: L-methylfolate as a trimonoamine modulator and antidepressant-augmenting agent. CNS spectrums, 12(10), 739-744.

- Silver H. Vitamin B12 levels are low in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2000; 37(1): 41-5.

- Saedisomeolia, Ahmad, et al. “Folate and vitamin B12 status in schizophrenic patients.” Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 16 (2011).

- Levine, J., Stahl, Z., Sela, B. A., Gavendo, S., Ruderman, V., & Belmaker, R. H. (2002). Elevated homocysteine levels in young male patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(10), 1790-1792.

- Muntjewerff, J. W., Kahn, R. S., Blom, H. J., & den Heijer, M. (2006). Homocysteine, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and risk of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Molecular psychiatry, 11(2), 143-149.

- Nishi, A., Numata, S., Tajima, A., Kinoshita, M., Kikuchi, K., Shimodera, S., … & Takeda, M. (2014). Meta-analyses of blood homocysteine levels for gender and genetic association studies of the MTHFR C677T polymorphism in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin, 40(5), 1154-1163

- Godfrey PS, Toone BK, Carney MW, Flynn TG, Bottiglieri T, Laundy M, et al. Enhancement of recovery from psychiatric ill- ness by methylfolate. Lancet. 1990;336(8712):392–5.

- Roffman, J. L., Lamberti, J. S., Achtyes, E., Macklin, E. A., Galendez, G. C., Raeke, L. H., … & Goff, D. C. (2013). Randomized multicenter investigation of folate plus vitamin B12 supplementation in schizophrenia. JAMA psychiatry, 70(5), 481-489.

- Levine J, Stahl Z, Sela BA, Ruderman V, Shumaico O, Ba- bushkin I, et al. Homocysteine-reducing strategies improve symptoms in chronic schizophrenic patients with hyperhomocy- steinemia. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60(3):265–9.

- Brown, H. E., & Roffman, J. L. (2014). Vitamin supplementation in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS drugs, 28(7), 611-622.

- Evans DL, Edelsohn GA, Golden RN: Organic psychosis without anemia or spinal cord symptoms in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:218–221

- Hart, R. J., & McCurdy, P. R. (1971). Psychosis in vitamin B12 deficiency. Archives of internal medicine, 128(4), 596-597.

- Payinda G, Hansen T: Vitamin B12 deficiency manifested as psychosis without anemia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:660–661

- Herr KD, Norris ER, Frankel BL: Acute psychosis in a patient with vitamin B12 deficiency and coincident cervical stenosis. Psychosomatics 2002; 43:234–236

- Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al: Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Assoc J 2001; 3:701–703

- Zhang, Y., Hodgson, N. W., Trivedi, M. S., Abdolmaleky, H. M., Fournier, M., Cuenod, M., … & Deth, R. C. (2016). Decreased brain levels of vitamin B12 in aging, autism and schizophrenia. PloS one, 11(1), e0146797.

- Goggans FC: A case of mania secondary to vitamin B12 deficiency. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:300–301

- Gomez-Bernal GJ, Bernal-Perez M: Vitamin B12 deficiency manifested as mania: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 9:238

- Jacobs LG, Bloom HG, Behrman FZ: Mania and a gait disorder due to cobalamin deficiency. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38:473–474

- Verbanck PM, Le Bon O: Changing psychiatric symptoms in a patient with vitamin B12 deficiency. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:182–183

- Brambilla P, Bellani M, Yeh PH, et al: White-matter connectivity in bipolar disorder. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009; 21:380–386

- Moore, E., Mander, A., Ames, D., Carne, R., Sanders, K., & Watters, D. (2012). Cognitive impairment and vitamin B12: a review. International psychogeriatrics, 24(04), 541-556.

- Morris MC, Schneider JA, Tangney CC: Thoughts on B-vitamins and dementia. J Alzheimer Dis 2006; 9:429–433

- Smith AD: The worldwide challenge of the dementias: a role for B vitamins and homocysteine? Food Nutr Bull 2008; 29: S143–S172

- Clarke, R. et al. (2007). Low vitamin B-12 status and risk of cognitive decline in older adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 86, 1384–1391.

- Wang HX, Wahlin A, Basun H, et al: Vitamin B12 and folate in relation to the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2001; 56:1188–1194

- Abyad, A. (2002). Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency among demented patients and cognitive recovery with cobalamin replacement. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 6, 254–260.

- Martin, D. C., Francis, J., Protetch, J. and Huff, F. J. (1992). Time dependency of cognitive recovery with cobalamin replacement: report of a pilot study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40, 168–172.

- Werder SF: Cobalamin deficiency, hyperhomocysteinemia, and dementia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2010; 6:159–195

- Hutto BR: Folate and cobalamin in psychiatric illness. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:305–314

- Leeming R J, Harpey JP, Brown SM, Blair JA. Tetrahydrofolate and hydroxycobalamin in the management of dihydropteridine reductase deficiency. J Ment Defic Res 1982;26:21-25.

- Spillmann, M., & Fava, M. (1996). S-Adenosylmethionine (Ademetionine) in psychiatric disorders. Cns Drugs, 6(6), 416-425.

- Bottiglieri, T., Hyland, K., & Reynolds, E. H. (1994). The clinical potential of ademetionine (S-adenosylmethionine) in neurological disorders. Drugs, 48(2), 137-152.

- Bottiglieri, T., Laundy, M., Crellin, R., Toone, B. K., Carney, M. W., & Reynolds, E. H. (2000). Homocysteine, folate, methylation, and monoamine metabolism in depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 69(2), 228-232.

- Mukherjee, R., & Brasch, N. E. (2011). Mechanistic studies on the reaction between cob (II) alamin and peroxynitrite: evidence for a dual role for cob (II) alamin as a scavenger of peroxynitrous acid and nitrogen dioxide. Chemistry–A European Journal, 17(42), 11805-11812.

- Wheatley, C. (2007). The return of the Scarlet Pimpernel: cobalamin in inflammation II—cobalamins can both selectively promote all three nitric oxide synthases (NOS), particularly iNOS and eNOS, and, as needed, selectively inhibit iNOS and nNOS. Journal of nutritional & environmental medicine, 16(3-4), 181-211.

- Birch, C. S., Brasch, N. E., McCaddon, A., & Williams, J. H. (2009). A novel role for vitamin B 12: Cobalamins are intracellular antioxidants in vitro. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 47(2), 184-188.

- livLee, Y. J., Wang, M. Y., Lin, M. C., & Lin, P. T. (2016). Associations between Vitamin B-12 Status and Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Diabetic Vegetarians and Omnivores. Nutrients, 8(3), 118.

- Altaie, A. (2009). Novel anti-oxidant properties of cobalamin.

- Scalabrino G, Buccellato FR, Veber D, Mutti E. New basis for the neurotrophic action of vitamin B12. Clin Chem Lab Med 2003; 41 :1435–7.

- Scalabrino G. Cobalamin (vitamin B12) in subacute com- bined degeneration and beyond: traditional interpretations and novel theories. Exp Neurol 2005; 192 :463–79.

- Scalabrino, G. (2009). The multi-faceted basis of vitamin B 12 (cobalamin) neurotrophism in adult central nervous system: lessons learned from its deficiency. Progress in neurobiology, 88(3), 203-220.

- Peracchi M, Bamonti Catena F, Pomati M, De Franceschi M, Scalabrino G. Human cobalamin deficiency: alterations in serum tumour necrosis factor- a and epidermal growth factor. Exp J Haematol 2001; 67 :123–7.